Where Am I Going, Where Have I Been? On Child Sex Abuse

This essay was originally published in my other newsletter, "Too Late For Questions?" It's important, so I'm sharing it with my Holy Chutzpah subscribers too.

Dear Readers & Fellow Writers,

Last week, I posted the following on Substack Notes:

Turning 51 next month.

Everything in the autobiographical past should make sense by now. Or so I thought.

Turns out there’s a new plot twist.

And the plot twist, chronologically speaking, happened over 40 years ago.

THIS, my friends, is why it takes so damn long to finish a memoir.

When the ground you’ve already crossed keeps cracking, the container holding your words does too.

I started a second Substack exactly one month prior to the events I’m about to share. I cannot believe the irony of this. The sheer prescience. Just before my autobiographical narrative would be upended, I chose this name for my second newsletter: Too Late For Questions?

Holy crap.

In February, I was contacted by an investigator who works for a law firm. The law firm represents victims of child sexual abuse, and the investigator was seeking information pertaining to a teacher from my elementary school where I attended from 1979 through 1985.

He didn’t need to tell me the teacher’s name. I knew immediately who it would be. The music teacher—Mr. W.

Within moments, I was sharing some details that I’ve always recalled from childhood but that I could never understand. These are stories my husband, Tomer, has been privy to over the past 30 years. I’ve thought of them as my “unsolved mysteries.”

I will provide an example.

When I was in first or second grade, my underwear suddenly went missing in the middle of the school day. I remember my horror and bewilderment and absolute panic as I stood in the bathroom stall trying to figure out where the underwear had gone.

I already suffered from severe Obsessive Compulsive Disorder at this time, and part of my morning ritual involved counting and checking all of my articles of clothing. I was a vigilant and conscientious child. I never forgot to wear underwear.

On the day my underwear went missing, not only could I not understand where it had gone, I suffered the remainder of the day irritated by the seam in my little-girl tights. The seam pressed against my bare genitals. It hurt.

As I shared this story with the investigator, I realized that the bathroom I was in when my underwear went missing was the one nearest the music room. And this bathroom wasn’t even on the same side of the school as the 1st and 2nd grade classrooms.

I had other memories too, and despite their implications, I remained totally disassociated from any appropriate affect given the nature of things.

Later, I reached out to some of my childhood friends. I had moved away in the seventh grade and fell out of touch with all of them (this was long before the internet or social media), but I am connected via Facebook to many of my former classmates. I’ve never interacted much with anyone from that phase of my life on social media, but I felt compelled to reach out.

It was shocking for me to discover that they did not recall the same things I did. For instance, I have always remembered Mr. W calling me “Boobie,” but in my memory, I took it for granted that he called all the girls this. But not one of the women I spoke with remembered Mr. W calling them “Boobie.”

And they hadn’t been afraid of him.

I had been terrified.

Although I was beginning to understand the reality of the situation, I felt no negative emotion. I remembered my fear of Mr W in the same way one recalls the details of a movie they’ve watched. It was as if I remembered someone else’s life.

When I started to joke around about the whole situation, I still failed to recognize that I was employing my favorite defense mechanism—a sense of humor.

“Well now we know why I can’t sing a note,” I said. “I was molested by the music teacher.”

I felt shame too, but it had nothing to do with sexual abuse itself. I felt humiliated that I hadn’t figured it out sooner.

“I feel stupid,” I said to my husband. “How did I not realize this years ago?”

“Well,” Tomer said, “You were solving a multi-dimensional crime. There was more than one perpetrator. More than one crime scene.”

Because my father also molested me, I never looked beyond him. There had always been odd details in my memory around elementary school, but I never got around to interrogating them. My father’s behavior was more than enough to explain the severity of my PTSD. This news about the music teacher felt like a revelation, as if the final puzzle pieces were clicking into place.

After speaking with the investigator, I carried on. I was fine. I went on a family vacation with my kids, and while wandering around theme parks, I thought about how I’d need to start my memoir all over again. Everything would require revision.

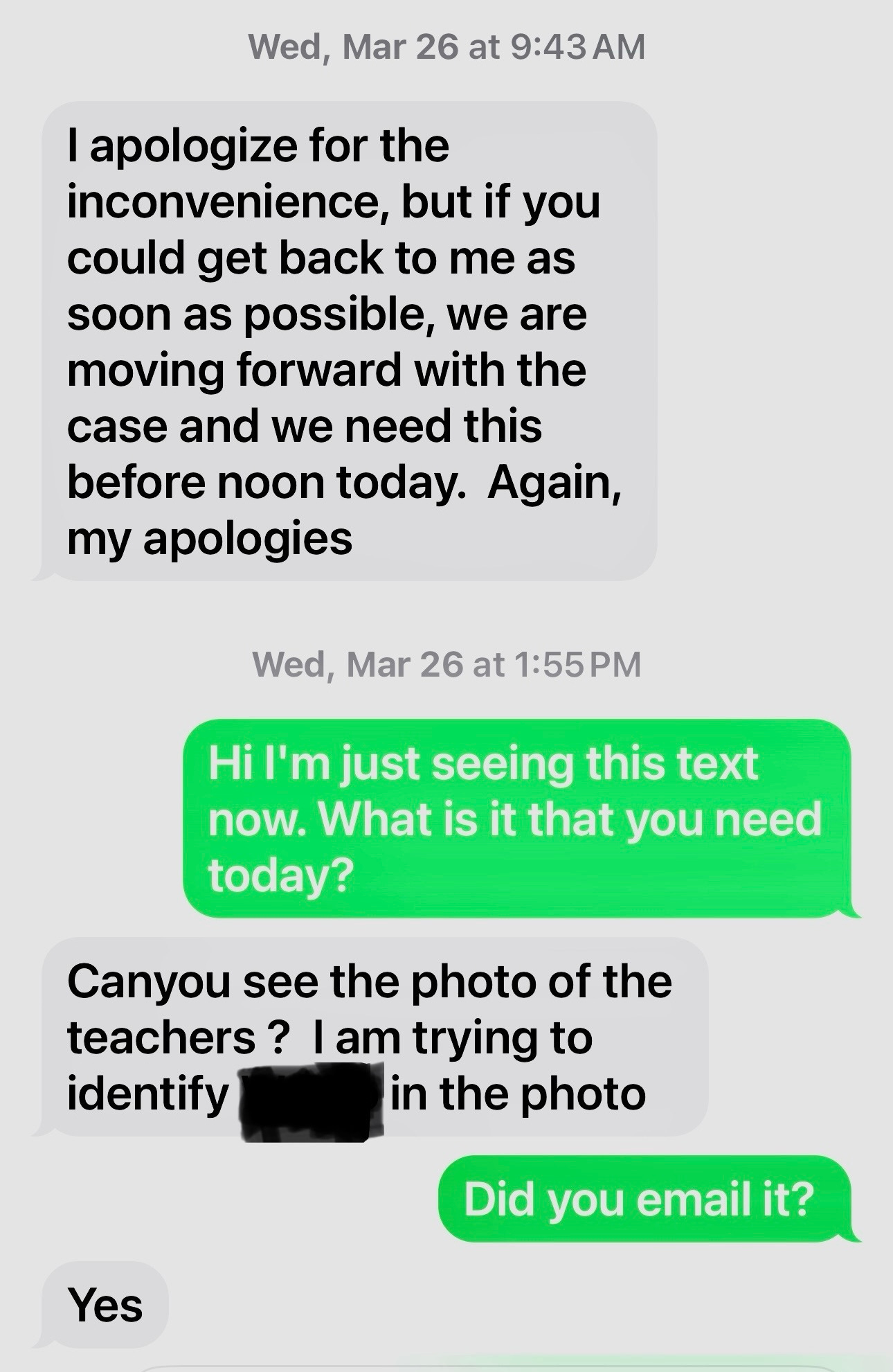

Then, eleven days ago, the investigator sent me an urgent text message:

I opened my email and saw a photo of the elementary school faculty from 1982-1983. The photo was grainy, but I found the music teacher immediately. He looked younger than I’d remembered, but so did everyone else, from the art teacher to the school librarian.

His image was unmistakable. Same glasses. Receding hairline was not quite as bad as I remembered—I pictured him as far more bald in my mind’s eye—but there he was. My breath caught in my throat.

After making the identification for the investigator, I felt a slight increase in anxiety, but I remained okay by focusing on how young all of the teachers looked. In my memory, my kindergarten and 3rd grade teachers looked ancient, but in the photo, they suddenly appeared youthful. They must’ve been younger then than I am now.

Meanwhile, I kept trying to recruit more people to speak with the investigator. He had mentioned several persons who he'd been trying to contact for over a year but who had not responded. I even posted an old class photo from 1st grade on my Facebook. I circled myself in the picture, hoping that seeing my tiny face and all the little children around me might inspire some of my Facebook friends to help out.

Unbeknownst to me, the case settled out of court. I can only assume that my input is what helped them strike a deal so soon after a years-long case, but nobody from the firm contacted me with this update, so I continued trying to further help. I kept staring at the faculty photograph—perhaps I could remember even more.

When my anxiety worsened, I suffered through it. I would face the memory in order to help the plaintiff—my former classmate who had also been one of my closest childhood friends at the time.

I started to be flooded by sensory details.

At night, I couldn’t sleep. I was up pacing all over the bedroom, terror rising in my chest. My arm froze up—I couldn’t move it—and I knew my body was remembering things. I looked down at my arm and realized it was frozen in the position identical to the time my arm was in a plaster cast following a fractured wrist in the 3rd grade.

I’m still not sleeping well. I’m still experiencing bodily sensations. The waves of terror come and go, and I’m flooded with seemingly benign memories too. I remember the look and feel of painted cinder blocks—I keep seeing and feeling those textured school walls.

There is no easy way out of this resurgence of PTSD symptoms; however, I am finally ripping the band aid off in a very public way. I made a Facebook post about all of this.

The Child Victims’ Act has already closed down in New York. I have no legal recourse, but I’ll be damned if I don’t find a way to claim my own life story and seek a path toward justice and healing.

I know that some of my family members remain upset by my disclosure on Facebook. I know that some family members were already upset following the publication of my personal essay in HuffPost in 2022. Some of my cousins do not believe the truth about my father. Others do not understand why I would want to speak ill of the dead. As if. As if I want this.

I have to speak up.

I feel sorry for all the people who loved my dad. I loved him too. I hated him as well.

Although rejection has been painful, I do not blame my extended family for cutting off from me. They don’t know how to navigate this. And why would they?

Our society doesn’t stone women and children for being victims of sex crimes, but it does demand silence. A silence that is soul crushing.

How sad for my family. How sad for me. You know who it’s not sad for? It’s not sad for my dead father. He died in 1989. He’s long gone.

And the woman who writes this post—that being me—is intelligent and kind, funny and interesting. People have literally chosen a dead man over me. Yes, my father had some great qualities too, but he also committed incest and brutalized his entire household with physical and verbal abuse.

As soon as I told my mother about the investigation, back in February, I noticed a change in her behavior toward me. She started getting off the phone more quickly. I wanted her to send me some childhood photos so that I could trigger memory to help the case, but she seemed agitated over this request. I couldn’t understand why. In fact, I thought she’d be relieved that this time wasn’t about my father. The music teacher! It practically seemed like something to celebrate, relatively speaking.

I tried to imagine the horror from Mom’s point of view. If this had G-d forbid happened to one of my children, I’d be devastated. And what mother wouldn’t be? Imagine all the mothers of the Penn State victims, Jeffrey Epstein, our Olympic gymnasts, the Catholic Church, and so forth. So many mothers are out there, not knowing how to support their adult children who have been harmed by child sex abuse. Just as they didn’t know how to help their children back when the abuse was happening.

I know how hard the fight is. I’ve personally been involved in multiple sex abuse cases, even beyond my professional experience in clinical social work. It is never easy. When I finally finish my book, people who read it will learn not only how pervasive child sex abuse is, but how the collective psychology of adults continues to enable it. It is a systemic problem.

What’s more: I do not envy any person related to a writer of memoir and personal essay. That‘s gotta suck. I’m sure it would’ve been easier for family members had I become a lawyer and found justice through legal means. Unfortunately for them, the nature of my work and personal healing requires exposure.

My very own children have endured suffering because of this abuse history, as has my beloved husband. How many inpatient hospitalizations were there during my son’s early childhood alone? I think there were three.

Enough is enough.

My story, traumatic as it is, is more than *just* an abuse memoir. My story is even greater than a personal investigation of my past.

My trauma narrative intersects with other challenging personal stories, all of them chapters connected to this early history including but not limited to: quitting a potential dance career, navigating a contested adoption, fighting my son’s high school when a teacher exhibited grooming behavior toward the male students.

And in addition to the darkness, my trauma history has also connected me with love and light. It gave me superpowers. I’ve met beautiful people who share this history and/or want to help protect the world’s children.

To be a victim of child sex abuse is to exist inside of an eternal paradox.

With this fresh lens of interrogation, I am casting off the burden of silence and shame and fear. I am truly sorry for anyone who suffers humiliation over the facts of my father’s abuse.

But here I am. Look at me. I am worthy of your attention. And you are worthy of mine.

I have spent years wrestling with what I can and cannot say. I even wrote about the ethics of memoir for Brevity Magazine’s blog—you can read that here.

I will continue to navigate my writing with as much care as possible for other persons who knew and loved my father, but I am no longer going to be doing so at the expense of my child-self. Nobody saved her back then, but I am going to do so now.

My hope for my mother is that she will see beyond the horror. That in my strength and resourcefulness, she will see the very love and care she gave me. She helped raise a warrior, and she should be proud.

And kudos to the little girl I once was.

Back in the 4th grade, I made a promise to my future self. Each day, I looked in the mirror, gazing deep into my eyes, thinking that I could send a message to myself in adulthood.

Promise to remember me. Promise to come back for me. Rescue me as soon as you can.

I survived child abuse by expanding the temporal space beyond the present moment. I time traveled and met my future self.

Here she is, ready to make good on her promises.

With my middle-aged hands, already wrinkled and worn, I am going to reach back through time and lift that child into my embrace. I am going to carry her forward into the present day. She cannot stay isolated and alone and terrified for another moment.

In order to commit more seriously to my book-length project, I will probably be posting with less frequency here, but I still intend to maintain both this newsletter and my other one, Too Late For Questions?

I want to note that I have received much love and tangible support in the last week, and it has come from persons near and far. I am full of love and gratitude for everyone who has reached out, offered resources, or simply wanted to extend a gesture of recognition for my humanity.

Lastly, I cannot overstate the sheer bewilderment I feel about this happening at the same time as my conversion to Judaism. It feels as if the worst evil—the evil of child sex abuse—has come to try and thwart my spiritual development. A fight of good versus evil.

My soul deserves a happy ending, and I intend to give it one, and more than that, I intend to uplift other victims of child sex abuse along the way.

Thank you for reading.

xoxo Jen xoxo

Hidden Water has groups for survivors, perpetrators, and parents of survivors. GREAT organization.

https://www.hiddenwatercircle.org

It's painful when family members don't want us to heal, just so they can preserve their "happy family" illusions. And it's hard to prioritize our own sanity and happiness over their acceptance and support. But, in the end, it's the best thing we can do for ourselves, and for our own children. I wish you healing and happiness. Looking forward to reading what you share with us.🧡